Week 4 - Apache Spark

Python Quick Guide

Variables

# Create a variable called a that points to 1>>> a = 1# Create another variable>>> b = 2# Get the value that the variable points to>>> a1>>> b2

Change the value of a variable after setting it:

# Make a point to 2 instead of 1>>> a = 2>>> a2

We can do something with a variable on the right side, then assign the result back to the same variable on the left side.

>>> a = 1>>> a = a + 1>>> a2

To do something to a variable (for example, to add something to it) we can also use +=, -=, = and /= instead of +, -, and /. The "advanced" %=, //= and **= also work.

>>> a += 2 # a = a + 2>>> a -= 2 # a = a - 2>>> a *= 2 # a = a * 2>>> a /= 2 # a = a / 2# Not limited to int>>> a = 'hello'>>> a *= 3>>> a += 'world'>>> a'hellohellohelloworld'

Operators

| Usage | Description | True examples |

|---|---|---|

a == b | a is equal to b | 1 == 1 |

a != b | a is not equal to b | 1 != 2 |

a > b | a is greater than b | 2 > 1 |

a >= b | a is greater than or equal to b | 2 >= 1, 1 >= 1 |

a < b | a is less than b | 1 < 2 |

a <= b | a is less than or equal to b | 1 <= 2, 1 <= 1 |

This table assumes that a and b are Booleans.

| Usage | Description | True example |

|---|---|---|

a and b | a is True and b is True | 1 == 1 and 2 == 2 |

a or b | a is True, b is True or they're both True | False or 1 == 1, True or True |

not can be used for negations. If value is True, not value is False, and if value is False, not value is True.

If, else and elif

print('Hello!')something = input("Enter something: ")if something = 'hello':print("Hello for you too!")elif something = 'hi'print('Hi there!')else:print("I don't know what," something, "means.")

List and list methods

>>> fruits = ['orange', 'apple', 'pear', 'banana', 'kiwi', 'apple', 'banana']>>> fruits.count('apple')2>>> fruits.count('tangerine')0>>> fruits.index('banana')3>>> fruits.index('banana', 4) # Find next banana starting a position 46>>> fruits.reverse()>>> fruits['banana', 'apple', 'kiwi', 'banana', 'pear', 'apple', 'orange']>>> fruits.append('grape')>>> fruits['banana', 'apple', 'kiwi', 'banana', 'pear', 'apple', 'orange', 'grape']>>> fruits.sort()>>> fruits['apple', 'apple', 'banana', 'banana', 'grape', 'kiwi', 'orange', 'pear']>>> fruits.pop()'pear'

Tuples A tuple consists of a number of values separated by commas:

>>> t = 12345, 54321, 'hello!'>>> t[0]12345>>> t(12345, 54321, 'hello!')>>> # Tuples may be nested:... u = t, (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)>>> u((12345, 54321, 'hello!'), (1, 2, 3, 4, 5))>>> # Tuples are immutable:... t[0] = 88888Traceback (most recent call last):File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment>>> # but they can contain mutable objects:... v = ([1, 2, 3], [3, 2, 1])>>> v([1, 2, 3], [3, 2, 1])

Sets

>>> basket = {'apple', 'orange', 'apple', 'pear', 'orange', 'banana'}>>> print(basket) # show that duplicates have been removed{'orange', 'banana', 'pear', 'apple'}>>> 'orange' in basket # fast membership testingTrue>>> 'crabgrass' in basketFalse

Dictionaries

>>> tel = {'jack': 4098, 'sape': 4139}>>> tel['guido'] = 4127>>> tel{'jack': 4098, 'sape': 4139, 'guido': 4127}>>> tel['jack']4098>>> del tel['sape']>>> tel['irv'] = 4127>>> tel{'jack': 4098, 'guido': 4127, 'irv': 4127}

For loop

for x in range(6):print(x)

While, break

i = 1while i < 6:print(i)if i == 3:break

Functions

@f1(arg)@f2def func(): pass# Equivalent of:def func(): passfunc = f1(arg)(f2(func))# E.Gdef whats_on_the_telly(penguin=None):if penguin is None:penguin = []penguin.append("property of the zoo")return penguin

HDFS Architecture (Hadoop Distributed File System)

- HDFS Architecture Guide: https://hadoop.apache.org/docs/r1.2.1/hdfs_design.html

- ZooKeeper: http://zookeeper.apache.org/

Ecosystem:

Introduction

- HDFS is a distributed file system - think of it as a bunch of computers networked together that form a cluster

- HDFS is designed to have a master-slave architecture, there is one master and slaves

- The Hadoop master is called the Name Node. The name "Name Node" is telling - it stores names and manages file system namespace

- Slaves are called Data Node - The name "Data Node" is telling - it manages the data of the file

- since HDFS is a File System - we can create directories and files using HDFS

Q: What happens when we create a file in HDFS?

- The Hadoop Client will send the request to the Name Node saying "Hey, I'd like to create this file"

- The Client will also provide the Client directory name and the file name

- When receiving the request, the Name Node will perform various checks e.g whether the directory already exists / not, whether the client has the right permissions or not to create the file etc.

- Name Node can perform these checks because it maintains an image of the entire HDFS namespace in memory (We call it in memory fsimage or file system image)

- If all the checks passed then the Name Node will create an entry for the new file and return success (to the client) so the file name creation ended, however it is empty.

- We have not started writing data to the file yet

- The vlient will create an fs data output stream and start writing data to it (hadoop streamer class - it buffers the data locally until you have a reasonable amount of data) - We call this a block. An HDFS data block.

- These HDFS block reaches out to Name Node asking for a block allocation (Asking the Name Node "Hey where do I store this block?")

- The Name Node doesn't store data, however it knows the amount of free disk space at each data node so it assigns a data node to store that block (128 MB . block usually - you can change it)

- So the Name Node will send back the data node name to the streamer

- Now the streamer knows where to send the data block and it sends it to the Data Node

- If the file is larger than 1 block, the streamer will reach out to the Name Node again for a new block allocation (may assign a different Data Node) - so the next block might go to a different Data Node.

- Once writing of the file is finished, the Name Node will commit all the changes

Fault Tolerance

- If some Data Nodes fail, what happens to your file?

- Hadoop creates a back up copy of each block and keeps it on some other Data Nodes

- If one copy is not available, you can read it from another copy

- In Hadoop we call this replication factor = 2

- We can set this replication factor on file to file basis and can change it even after creating a file

- Replication factor of 2 will create 2 copies of each block and Hadoop will keep these two blocks on two different machines

- Typically we set this replication faoctor to 3

What happens if the entire rack fails?

- All three copies would be gone

- Now, you can configure Hadoop to be Rack Aware - then Hadoop wil place at least 1 copy in a different rack to protect you from rack failures

- Each Data Node sends a periodic heartbeat to Name Node and spot all Data Nodes that failed

- In such case the Name Node will initiate the replication of the block and bring it back to three replicas

- So the Name Node continously tracks the replication of each block and initiates replication when necessary

- The problem is that replication factor reduces the storage capacity of your cluster and increases the cost

- Hadoop offers Storage Policies and Erasure Coding as an alternative to replication - however replication is the traditional method

- High Availability refers to the uptime of the system - shows the percentage of time the service is up.

- every enterprise wants a 99.999% uptime for their critical systems

- So note that block failures do not take your cluster down, do not affect availability

- However, when Name Node fails we cannot use the Hadoop cluster - we cannot read/write anything to the cluster

- So the Name Node is a single point of failure SPOF in the Hadoop cluster

- So we want to be protected against Name Node failures - the solution is Backup

- In this case we need to make a backup of the HDFS Namespace information and the standby Name Node machine

HDFS Goals

Hardware Failure Hardware failure is the norm rather than the exception. An HDFS instance may consist of hundreds or thousands of server machines, each storing part of the file system’s data. The fact that there are a huge number of components and that each component has a non-trivial probability of failure means that some component of HDFS is always non-functional. Therefore, detection of faults and quick, automatic recovery from them is a core architectural goal of HDFS.

Streaming Data Access Applications that run on HDFS need streaming access to their data sets. They are not general purpose applications that typically run on general purpose file systems. HDFS is designed more for batch processing rather than interactive use by users. The emphasis is on high throughput of data access rather than low latency of data access. POSIX imposes many hard requirements that are not needed for applications that are targeted for HDFS. POSIX semantics in a few key areas has been traded to increase data throughput rates.

Large Data Sets Applications that run on HDFS have large data sets. A typical file in HDFS is gigabytes to terabytes in size. Thus, HDFS is tuned to support large files. It should provide high aggregate data band and scale to hundreds of nodes in a single cluster. It should support tens of millions of files in a single instance.

Simple Coherency Model HDFS applications need a write-once-read-many access model for files. A file once created, written, and closed need not be changed. This assumption simplifies data coherency issues and enables high throughput data access. A MapReduce application or a web crawler application fits perfectly with this model. There is a plan to support appending-writes to files in the future.

“Moving Computation is Cheaper than Moving Data” A computation requested by an application is much more efficient if it is executed near the data it operates on. This is especially true when the size of the data set is huge. This minimizes network congestion and increases the overall throughput of the system. The assumption is that it is often better to migrate the computation closer to where the data is located rather than moving the data to where the application is running. HDFS provides interfaces for applications to move themselves closer to where the data is located.

Portability Across Heterogeneous Hardware and Software Platforms HDFS has been designed to be easily portable from one platform to another. This facilitates widespread adoption of HDFS as a platform of choice for a large set of applications.

NameNode and DataNodes

HDFS has a master/slave architecture. An HDFS cluster consists of a single NameNode, a master server that manages the file system namespace and regulates access to files by clients. In addition, there are a number of DataNodes, usually one per node in the cluster, which manage storage attached to the nodes that they run on. HDFS exposes a file system namespace and allows user data to be stored in files. Internally, a file is split into one or more blocks and these blocks are stored in a set of DataNodes. The NameNode executes file system namespace operations like opening, closing, and renaming files and directories. It also determines the mapping of blocks to DataNodes. The DataNodes are responsible for serving read and write requests from the file system’s clients. The DataNodes also perform block creation, deletion, and replication upon instruction from the NameNode.

and have strictly one writer at any time

- The NameNode makes all decisions regarding replication of blocks. It periodically receives a Heartbeat and a Blockreport from each of the DataNodes in the cluster. Receipt of a Heartbeat implies that the DataNode is functioning properly. A Blockreport contains a list of all blocks on a DataNode

in 2013. It grows by 40% every year, and by 2020 the IDC expects it to be as large as 44 Zettabytes, amounting to a single bit of data for every star in the physical universe.

- We have a lot of data, and we aren’t getting rid of any of it. We need a way to store increasing amounts of data at scale

- Even if Excel could store that much data, not many desktop computers have enough hard drive space for that anyway.

- One computer works well for watching movies or working with spreadsheet software. However, there are things a computer is not powerful enough to perform - e.g data processing. Single machines do not have the power and resources to perform computations on huge amounts of information or the user does not have time to wait for the computation to finish

" ="300">

" ="300">

- A cluster or group, of computers, pools the resources of many machines together, giving us the ability to use all the cumulative resources as if they were a single computer.

- A group of machines alone is not powerful, you need a framework to coordinate work across them

- Spark does just that! - Coordinating and managing the execution of tasks on data across a cluster of computers.

Thank the cosmos we have Spark!

Brief history of Spark - If you'd like to see the big picture.

Glossary

To understand Spark, first familiarize yourself with these terms:

| Glossary | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cluster | A group of computers pooling the resources of many machines together, giving us the ability to use all the cumulative resources as if they were a single computer. YARN or Mesos or Spark's standalone cluster manager. We then submit Spark Applications to these cluster managers |

| Language APIs | Make it possible to run code using programming languages (Scala, Python, Java, R, SQL) |

| Computing Engine | Spark handles loading data from storage systems and performing computation on it, not being a permanent storage as the end itself. You can use Spark with a wide variety of storage systems such as Azure Storage and Amazon S3, distributed file systems such as Apache Hadoop, key-value stores such as Apache Cassandra and message buses such as Apache Kafka. However, Spark does not store data long-term itself. |

| Unified | Spark is designed to support a wide range of data analytics tasks over the same computing engine and with a consistent set of APIs. Real world data analytics tasks tend to combine many different processing types and libraries. |

| Libraries | Spark supports standard libraries and external libraries. Spark includes libraries for SQL, and structured data SparkSQL, machine learning (MLlib), stream processing (Spark Streaming and the newer Structured Streaming), and graph analytics (GraphX). Beyond these libraries there are a hundreds of open source external libraries. (spark-packages.org) |

| Parallel Processing | Large problems divided into smaller ones, which can then be solved at the same time |

...Now, What's Spark?

Apache Spark is a unified computing engine and a set of libraries for parallel data processing on computer clusters that supports programming languages like R, Python, Java and Scala and libraries ranging from SQL to streaming and machine learning and runs everywhere from a laptop to a cluster of thousands of servers making it easy to scale up to big data processing or incredibly large scale

Spark Core: This is the heart of Spark, and is responsible for management functions such as task scheduling. Spark Core implements and depends upon a programming abstraction known as Resilient Distributed Datasets (RDDs), which is outside the scope of this class.

Spark SQL: This is Spark’s module for working with structured data, and it is designed to support workloads that combine familiar SQL database queries with more complicated, algorithm-based analytics. Spark SQL supports the open source Hive project, and its SQL-like HiveQL query syntax. Spark SQL also supports JDBC and ODBC connections, enabling a degree of integration with existing databases, data warehouses and business intelligence tools. JDBC connectors can also be used to integrate with Apache Drill, opening up access to an even broader range of data sources.

Spark Streaming: This module supports scalable and fault-tolerant processing of streaming data, and can integrate with established sources of data streams like Flume (optimized for data logs) and Kafka (optimized for distributed messaging). Spark Streaming’s design, and its use of Spark’s RDD abstraction, are meant to ensure that applications written for streaming data can be repurposed to analyze batches of historical data with little modification.

MLlib: This is Spark’s scalable machine learning library, which implements a set of commonly used machine learning and statistical algorithms. These include correlations and hypothesis testing, classification and regression, clustering, and principal component analysis.

GraphX: This module began life as a separate UC Berkeley research project, which was eventually donated to the Apache Spark project. GraphX supports analysis of and computation over graphs of data, and supports a version of graph processing’s Pregel API. GraphX includes a number of widely understood graph algorithms, including PageRank.

Use cases

Use cases Stream processing This data arrives in a steady stream from multiple sources simultaneously. Streams of data related to financial transactions can be processed in real time to identify – and refuse – potentially fraudulent transactions. Machine learning Spark’s ability to store data in memory and rapidly run repeated queries makes it a good choice for training machine learning algorithms. Interactive analytics Business analysts and data scientists want to explore their data by asking a question and viewing the results. This interactive query process requires systems such as Spark that are able to respond and adapt quickly. Data integration Data produced by different systems across a business is rarely clean or consistent enough to simply and easily be combined for reporting or analysis. Spark is used to reduce the cost and time required for this ETL process.

Launching Spark's Interactive Console

You can grab Spark from here, altough we will use Databricks in this course: https://spark.apache.org/downloads.html

Spark runs on the JVM (Java Virtual Machine) so you need to install Java to run it. If you want to use the Python API, you will also need a Python interpreter. If you want to use R, you will need a version of R on your machine.

| Python | Scala | SQL |

|---|---|---|

| ./bin/pyspark | ./bin/spark-shell | ./bin/spark-sql |

| after you have done that type "spark" and press Enter. You will see the "SparkSession" object printed | after you have done that type "spark" and press Enter. You will see the "SparkSession" object printed | after you have done that type "spark" and press Enter. You will see the "SparkSession" object printed |

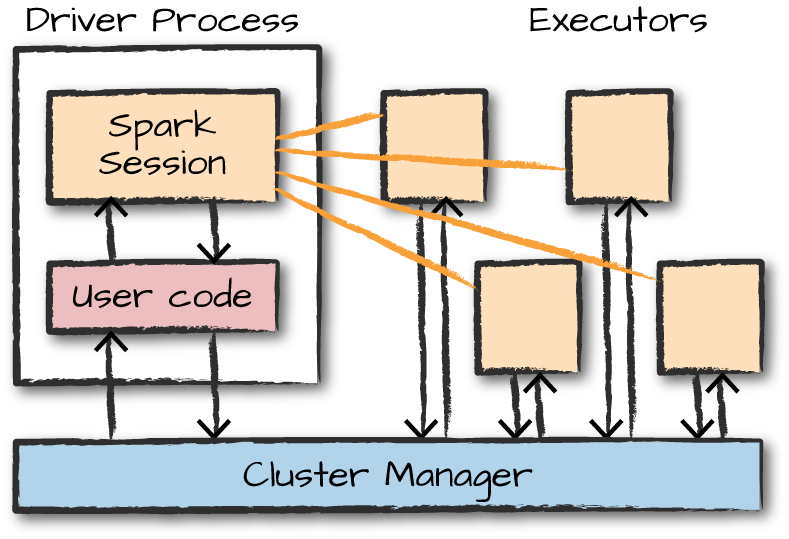

- SparkSession: You can control your Spark Application through a driver process called the SparkSession. The SparkSession is the way Spark executes user-defined manipulations across the cluster. There is a one-to-one correspondance between a SparkSession and a SparkApplication. SparkSession and Language APIs relationship:

- Spark Application Architecture: Spark applications consist of a driver process and a set of executor processes.

Driver is on the left, four executors on the right. It demonstrates how the cluster manager controls physical machines and allocates resources to Spark Applications. This can be one of three cluster managers ( YARN, Mesos, Spark's standalone cluster manager). This means that there can be multiple Spark Applications running on a cluster at the same time.

Note: Spark, in addition to a cluster mode, also has a local mode. The driver and the executor are simply processes, this means they can live on the same machine or different machines. Local Mode - Driver and executor run as threads on your individual computer in stead of a cluster.

| Driver Process | Executor Process |

|---|---|

| The heart of a Spark Application, maintains all relevant information during the lifetime of the application. Runs of your main() function, sits on a node in the cluster, and is responsible for: Maintaining information about the Spark Application. Responding to a user's program or input. Analyzing, distributing and scheduling work across the executors | Responsible for actually carrying out the work that the (<-) driver assigns them. Each executor is responsible for: Executing code assigned to it by the driver. Reporting the state of the computation on that executor BACK to the driver node. |

Key Takeaways:

- Spark employs a cluster manager that keeps track of the resources available

- The driver process is responsible for executing the driver program's commands across the executor to complete a given task

The executor only runs Spark code. However, the driver can be driven from a number of different languages through Spark's Language APIs. (Scala, Java, Python, R)

API Overview

Structured APIs are a tool for manipulating all sorts of data, from unstructured log files to semi-structured CSV files and highly structured Parquet (Apache Parquet is a columnar storage format available to any project in the Hadoop ecosystem, regardless of the choice of data processing framework, data model or programming language) files. These APIs refer to three core types of distributed collection APIs:

- Datasets

- DataFrames

- SQL Tables and Views

Majority of the Structured APIs apply to both batch and streaming computation. This means that when you work with the Structured APIs, it should be simple to migrate from batch to streaming or vice versa with little to no effort. Structured APIs are the fundamental abstraction used to write the majority of data flows.

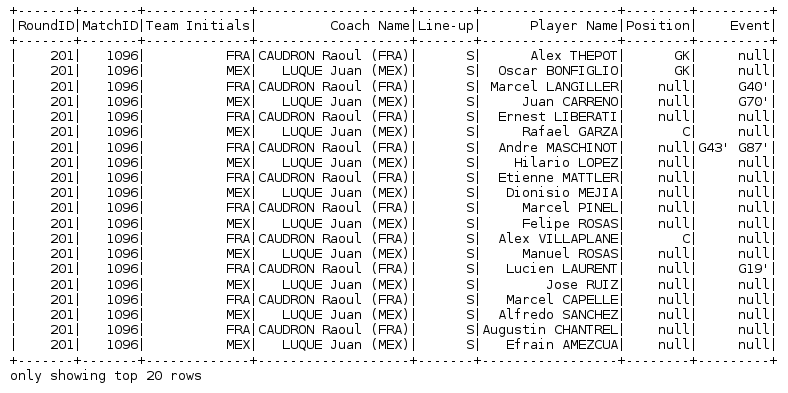

DataFrames

For those familiar with the DataFrames API in other languages like R or pandas in Python, this API will make them feel right at home. In this course, we are going to focus on the DataFrame API and skip Datasets & RDDs - but to explain DataFrames - we need to understand RDDs a little.

A Dataframe is a distributed collection of rows under named columns. In simple terms, it looks like an Excel sheet with Column headers, or you can think of it as the equivalent to a table in a relational database or a DataFrame in R or Python.

Note: A DataFrame is an abstraction on top of RDDs. An RDD is broken down into partitions and a DataFrame is an abstraction on top of RDDs hence DataFrame is also partitioned. DataFrames ultimately compile down to RDDs.

DataFrames (and Datasets) are distributed table-like collection with well-defined rows and columns. Each column must have the same number of rows as all the other columns although you can use null to specify the absence of a value and each column has type information that must be consistent for every row in the collection. To Spark, DataFrames (and Datasets) represent immutable, lazily evaluated plans(transformations) that specify what operations to apply to data residing at a location to generate some output. When we perform an action on a DataFrame, we instruct Spark to perform the actual transformations and return the results. These represent plans of how to manipulate rows and columns to compute the user's desired result.

- To allow every executor to perform work in parallel, Spark breaks up the data into chunks called partitions.

- A partition is a collection of rows that sit on one physical machine in your cluster

- A DataFrame’s partitions represent how the data is physically distributed across the cluster of machines during execution

- If you have one partition, Spark will have a parallelism of only one, even if you have thousands of executors

- If you have many partitions but only one executor, Spark will still have a parallelism of only one because there is only one computation resource.

Lazy Evaluation

- Spark waits until the very last moment to execute the graph of computation instructions

- Spark will not modify data immediately when you express some operation, you build up a plan of transformations that you would like to apply to your source data

- Spark optimizes the entire data flow from end to end

- Predicate Pushdown - Spark will attempt to move filtering of data as close to the source as possible to avoid loading unnecessary data into memory

- DataFrames have a set of columns with an unspecified number of rows -> reading data is a transformation and is a lazy operation

- Spark only peeks at a couple of rows to try guess what type each column should be

Actions

- Transformations allow us to build up our logical transformation plan

- To trigger the computation we run an action

- Action instructs Spark to compute a result from a series of transformations

- The simplest action is count, which gives us the total number of records in the DataFrame

- There are three kinds of actions

- Actions to view data in the console

- Actions to collect data to native objects in the respective language

- Actions to write to output data sources

Transformations:

- Transformations are the core of how you express your business logic using Spark. There are two types of transformations:

- those that specify narrow dependencies, which are those for which each input partition will contribute to only one output partition

- and those that specify wide dependencies (shuffles), where we have input partitions contributing to many output partitions

- Narrow transformations can be performed in-memory, whereas for shuffles, Spark writes the results to disk

- Spark will not act on transformations until we call an action, that's why we say that they are lazily evaluated

- Lazy evaluation means that Spark will wait until the very last moment to execute the graph of computation instructions

There are two types of transformations: Narrow dependencies and Wide dependencies

Narrow dependencies:

- Each input partition will contribute to only one output partition

divisBy2 = myRange.where("number % 2 = 0")

- In the above code the "where" statement specifies a narrow dependency, where only one partition contributes to at most one output partition. (see the map, filter part of the picture below)

- Automatically performs an operation called pipelining, meaning that if we specify multiple filters on DataFrames, they will all be performed in-memory

Wide dependencies:

- input partitions contributing to many output partitions

- Also referred to as "Shuffle" whereby Spark will exchange partitions across the cluster

- When we perform a shuffle, Spark writes the results to disk.

divisBy2 = myRange.where("number % 2 = 0")

- In specifying this action, we started a Spark job that runs our filter transformation (narrow transformation) then an aggregation (wide transformation) that performs the counts on a per partition basis, and then collect, which brings our result to a native object in the respective language

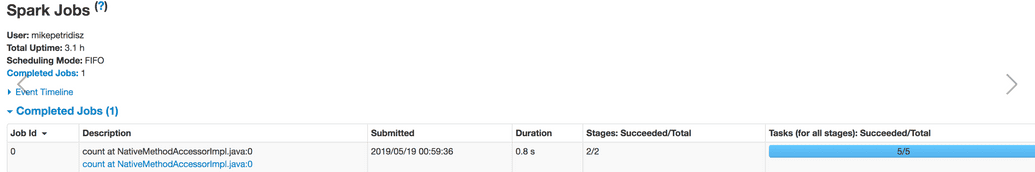

- Spark UI: (for monitoring the progress of a job) Local mode: available on port 4040 of the driver node. http://localhost:4040

- Spark job: represents a set of transformations triggered by an individual action, and you can monitor that job from Spark UI

Overview of Structured API Execution

How is the code actually executed across a cluster? Here’s an overview of the steps:

- Write DataFrame/Dataset/SQL Code

- If valid code, Spark converts this to a Logical Plan

- Spark transforms this Logical Plan to a Physical Plan, checking for optimizations along the way

- Spark then executes this Physical Plan on the cluster

Read Data

df = spark.read.options(header = "true", \inferSchema = "true", \nullValue = "NA", \timestampFormat = "yyyy-MM-dd'T'HH:mm?:ss", \mode = "failfast").csv("/PATH/TO/FILE")

DataFrame Operations

a DataFrame consists of:

A series of records (like rows in a table), that are of type Row

A number of columns (like columns in a spreadsheet) that represent a computation expression that can be performed on each individual record in the Dataset

Schemas define the name as well as the type of data in each column

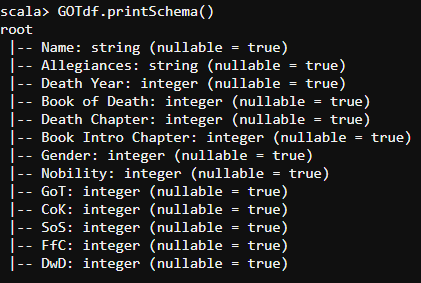

- A schema defines the column names and types of a DataFrame

- We can either let a data source define the schema or we can define it explicitly ourselves

- To check the schema:

df.printSchema()

A schema is a StructType made up of a number of fields, StructFields, that have a name, type, a Boolean flag which specifies whether that column can contain missing or null values, and, finally, users can optionally specify associated metadata with that column.

Partitioning of the DataFrame defines the layout of the DataFrame or Dataset’s physical distribution across the cluster.

- The partitioning scheme defines how that is allocated. You can set this to be based on values in a certain column or nondeterministically

Columns and Expressions

- Columns in Spark are similar to columns in a spreadsheet, R dataframe, or pandas DataFrame. You can select, manipulate, and remove columns from DataFrames and these operations are represented as expressions

- To construct columns we can use the

withColumnfunction

df.withColumn('newage',df['age']).show()df.withColumn('half_age',df['age']/2).show()

Records and Rows

- In Spark, each row in a DataFrame is a single record. Spark represents this record as an object of type Row

- Spark manipulates Row objects using column expressions in order to produce usable values

- Row objects internally represent arrays of bytes

We can see a row by calling

firstorhead(1)in a DataFrame

df.first()df.head(1)

DataFrame Transformations

selectallows you to do the DataFrame equivalent of SQL queries on a table of data:

df.select("age").show(2)

- We can register the DataFrame as a SQL temporary view (It's thde equivalent of

SELECT AGE FROM PEOPLE LIMIT 2)

df.createOrReplaceTempView("people")

Filtering Rows Example:

df.filter( (df["Close"] < 200) | (df['Open'] > 200) ).show()

Sorting Rows

For sorting we can use sort and orderBy which function similarly:

df.sort("Sales").show()df.orderBy("Sales").show()

Grouping

df.groupBy("Company")df.groupBy("Company").count().show()df.groupBy("Company").mean().show()df.groupBy("Company").min().show()

DataFrame Aggregations

- Aggregating is the act of collecting something together and is a cornerstone of big data analytics. In an aggregation, you will specify a key or grouping and an aggregation function that specifies how you should transform one or more columns

- This function must produce one result for each group, given multiple input values.

All aggregations are available as functions, most aggregation functions can be found here: http://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.sql.functions$

countfunction allows us to specify a specific column to count

df.select(count("Sales")).show()

countdistinctfunction gives us the number of unique groups

from pyspark.sql.functions import countDistinctdf.select(countDistinct("Sales")).show()

Methods

http://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.sql.functions$ http://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.sql.DataFrameStatFunctions http://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.sql.Column http://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.sql.Dataset

Joins

Joins are an essential part of nearly all Spark workloads. Spark’s ability to talk to different data means that you gain the ability to tap into a variety of data sources across your company

Whereas the join expression determines whether two rows should join, the join type determines what should be in the result set. There are a variety of different join types available in Spark for you to use such as (list not-exhaustive):

Inner joins (keep rows with keys that exist in the left and right datasets)

Outer joins (keep rows with keys in either the left or right datasets)

Left outer joins (keep rows with keys in the left dataset)

Right outer joins (keep rows with keys in the right dataset)

Key Takeaways:

- Lazy Evaluation in Spark means that the execution will not start until an action is triggered.

- Transformations are lazy in nature i.e., they get execute when we call an action. They are not executed immediately. Two most basic type of transformations is a

map(),filter(). - Actions are like a valve and until action is fired, the data to be processed is not even in the pipes, i.e. transformations. Only actions can materialize the entire processing pipeline with real data.

Example

https://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/6/6.006/s08/lecturenotes/files/t8.shakespeare.txt

A simple program that performs a word count on the collected works of Shakespeare

from pyspark import SparkContext, SparkConfconf = SparkConf().setAppName('MyFirstStandaloneApp')sc = SparkContext(conf=conf)text_file = sc.textFile("./shakespeare.txt")counts = text_file.flatMap(lambda line: line.split(" ")) \.map(lambda word: (word, 1)) \.reduceByKey(lambda a, b: a + b)print ("Number of elements: " + str(counts.count()))counts.saveAsTextFile("./shakespeareWordCount")

Sources: To be finished